Learning in Digital Worlds

Gamifying student behaviour

Gamification is commonly defined as the use of game-design elements in non-game contexts. Game design elements include, but are not restricted to, achievements, badges, timers, avatars, but also something like narration (a story). Therefore, gamification includes a wide range of activities and applications, from quiz software like Kahoot to classroom management tools like ClassDojo and Classcraft. But what happens when classroom management is turned into a game?

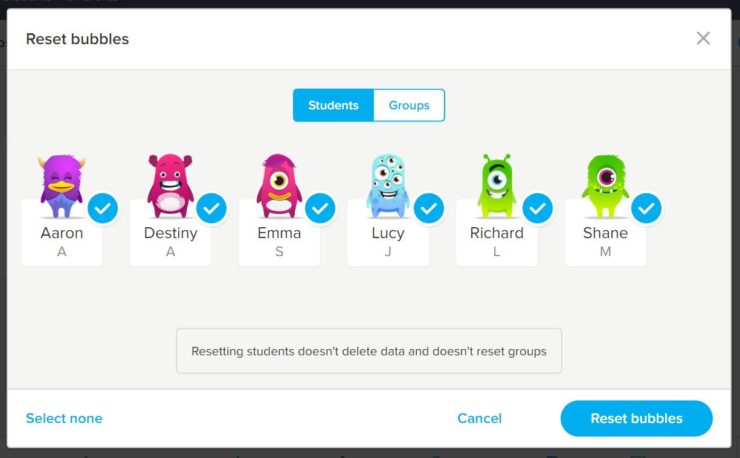

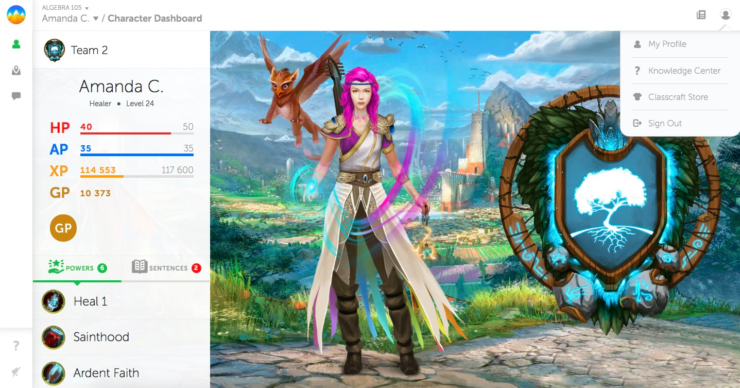

Both ClassDojo and Classcraft can be classified as behaviour management tools. In ClassDojo (see above) students have an avatar that can be awarded appropriately by the teacher once the student has demonstrated good behaviour. ClassDojo is most commonly used in primary schools and it has now evolved into an extensive tool for sharing school life with parents. Classcraft (see below) relies more explicitly on fantasy elements and online multiplayer games. In Classcraft students can choose an avatar of a certain class, each with different powers, as they are grouped together in teams. A healer, for instance, can restore the health of a teammate and a mage can restore Action Points so that the other characters can perform their actions. Teachers can reduce Health Points for bad behaviour or they can award students Gold Points which they can use to buy new gear. Teams can battle against bosses. If a team member dies in battle, they receive a (real world!) sentence.

There are many critiques regarding these kinds of gamification based on point systems and achievements. One of those critiques is that they rely too much on behaviorist interpretations of human behaviour. Behaviorism is a psychological philosophy that originated in the United States in the 1950’s. It sees the human mind as a black box: we can only understand human behaviour based on input and output, behaviour being the output of a certain stimulus. The most famous behaviorist, B.F. Skinner, conducted experiments with pigeons and rats to test how behaviour can be learned by rewards in a process called reinforcement. The critique of gamification then, is that it is too often seen as a mere tool for the reinforcement of behaviour, especially in marketing and advertising. Point systems and achievement are used to guide consumers’ (or students’) behaviour into desirable outcomes, just like Skinner conditioned his rats and his pigeons.

But is the conditioning of students necessarily a problem? Many teacher will know that behaviour management in the classroom is mostly based on reinforcement techniques, either positive ones (promising students play time if they work well) or negative ones (giving naughty students an additional assignment). Gamified applications like ClassDojo and Classcraft use a game vocabulary and interface, but their basic principle is not very different to what teachers have been doing for centuries (in more or less harsh forms) – or is it?

Some authors argue that applications like Classcraft help students understand their behaviour in the classroom by using the world of a game as a metaphor: exams are battles and someone’s HP is indicative of someone’s behaviour. It is implied here that a world students are familiar with (the game world and its design elements) helps them interpret and manage their behaviour more effectively. This reminded me of Baudrillard’s theory of the hyperreal. Baudrillard states that we increasingly experience reality through representations; through television, movies and nowadays social media. This, he argues, makes representations (movies, pictures) and simulations (games) more relevant than the real as they increasingly merge with reality. A good example is that our ideas of how guns sound is shaped by Hollywood movies to the extent that when we hear real guns they often sound fake. Another example is how we give meaning to our romantic lives by referring to movies or series. The idea of romance in movies, furthermore, refers back to other (older) movies and not to an underlying reality.

Classcraft can be seen as providing a hyperreal experience to the classroom in which behaviour gets meaning through the world of a game. A simulation (a game) is used to make sense of the real world (the classroom environment), because apparently we need an intermediate to connect with reality, to make sense of it all. The question we should then pose ourselves is: what is the value of our real life actions if they are perceived through the lens of a simulation? What does it mean when a student’s behaviour affects their avatar rather than their own persona? What does it mean if students evaluate how ‘good’ they have been by the amount of Health Points or Action Points instead of their real-life actions. Are we beginning to loose touch with morality?

The pessimistic Baudrillard would certainly agree with this. But what do you think? Do you think giving students ‘virtual’ rewards helps them improve their behaviour? What are you teaching by managing student behaviour via a game? I am curious to hear from teachers who use either ClassDojo or Classcraft!